The Legendary Artists Of Tanzania

A Sculptor who comes from a long, storied line of stone artisans March 15th, 2020 2:30 pm – 5:30 pm by Alan Donovan of the Murumbi Trust, this exhibition is part a series of exhibitions by the continent’s pioneer artists he has been presenting for the past twelve years at NMK Nairobi Gallery.

When I first arrived in Kenya in March 1970, after my TransAfrican trip overland from Paris, I stopped in Nakuru late in the afternoon. After a cold Tusker at an outdoor café I noticed a vendor selling soapstone items on the pavement. There was a twisted candle holder, a clever frog in the box which had a snake that jumped out when you pushed the frog on top, an elephant with trunk down and a leaf-shaped dish. They were all in the soft pink and purple hues with a tinge of gold found in Kenyan soapstone. I continued to see similar items on the streets of Nairobi while I applied for a license to go up to Kenya’s Northern Frontier where I spent several months mostly amongst the nomadic Turkana.

When I first arrived in Kenya in March 1970, after my TransAfrican trip overland from Paris, I stopped in Nakuru late in the afternoon. After a cold Tusker at an outdoor café I noticed a vendor selling soapstone items on the pavement. There was a twisted candle holder, a clever frog in the box which had a snake that jumped out when you pushed the frog on top, an elephant with trunk down and a leaf-shaped dish. They were all in the soft pink and purple hues with a tinge of gold found in Kenyan soapstone. I continued to see similar items on the streets of Nairobi while I applied for a license to go up to Kenya’s Northern Frontier where I spent several months mostly amongst the nomadic Turkana.

It was during an exhibition of my Northern frontier art at Studio Arts ’68 that I met Kenya’s most famous cultural icon, the late former Vice President Joseph Murumbi, whose collections form the basis of the Kenya National Archives and the National Museums of Kenya.

Later as the Exhibitions Officer of Studio Arts 68, I met the supplier of the gallery’s soapstone art, Nelson Ongesa. He was from the town of Tabaka near Kisii, famous for its soapstone quarries. He brought in objects that were similar to those I had seen on the streets of Nakuru when I first entered Kenya. Then he showed me something different which he had created, which was a small “sun faced lion”. This was the start of a long association with the Kisii carvers. I started working with Nelson to produce new designs to augment those that they had been first produced for the local missionaries at Kisii.

It was in l972, that Murumbi confided in me about his dream to set up a Pan African Center in Nairobi. He wanted local people and tourists could see the creativity of the entire continent as he had seen during his time as Foreign Minister when he had set up the Country’s missions and high commissions. The result was African Heritage, the continent’s first Pan African Gallery and restaurant. It opened its doors near the end of 1972.

The opening exhibition of African Heritage presented artists from both the East and the West of Africa. It featured the formidable talented artist and printmaker, one of Nigeria’s most acclaimed artists, Bruce Onobrakpeya, who had first come to Kenya with the Nigerian Festival that I had staged in January 1972. This festival had marked the very first show in Kenya with all African fabrics, all African models and all African Jewellery.

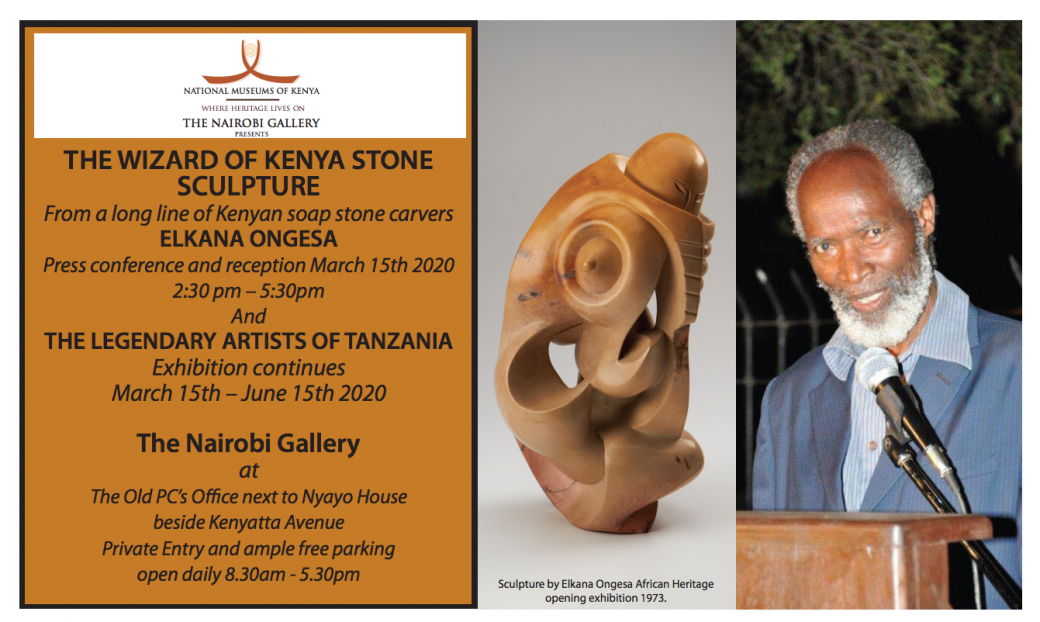

Representing East Africa in this premier exhibition was a young aspiring artist and sculptor studying for a degree in East African Stone Sculpture at the University of Nairobi. Elkana Ongesa was the first in a long line of stone carvers to acquire a college education. He was the nephew of Nelson Ongesa of the “sun-faced lion” whom I had come to know quite well after several visits to Kisii and the nearby quarries at Tabaka. Murumbi was infatuated by the dignified Bruce Onobrakpeya and his accomplished large body of work. He was also intrigued by Nelson’s nephew, the young emissary from the Kisii carvers, Elkana Ongesa.

The opening exhibition of African Heritage brought international acclaim to the two artists of diverse ages and talents. Murumbi was a fervent supporter of Elkana just as he had been of the Dean of East African artists, Francis Nnaggenda. At the opening of African Heritage, Murumbi noted that he was the ONLY African to buy Francis’s works. He owned five of them. He implored the mayor of Nairobi, Margaret Kenyatta, who opened the exhibition, and the Nairobi City Council. This fell on deaf ears. For lack of buyers, Francis moved to Texas in the USA, returning two decades later to take up the position as Chancellor of the Margaret Trowell School of Applied and Fine Arts in Kampala.

The story was the same with Elkana. Few local collectors emerged to buy his works and he largely depended on sales from African Heritage where his uncle Nelson had become chief supplier of soapstone items along with many other members of his extended family.

Murumbi was fascinated by Elkana’s bird forms. One of those bird sculptures he bought from Elkana now occupies a prominent place in the Kenya National Archives. It stands next to the huge “Baga” mask that brought Murumbi and myself together to open African Heritage. It became the famous logo of the firm, appearing on all of its yellow shopping bags, receipts, and letterheads.

It was that same bird that The Director of UNESCO saw at a dinner party at the Murumbi house in Muthaiga in the days before the government of the day had the house demolished. He asked Murumbi to commission a similar bird for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, where it stands today. Other statues by Elkana are on display at the United Nations in New York City, at Coca Cola HQ in Atlanta and in Changchun, China.

After Murumbi fell sick, having survived several strokes, he was evacuated from his home near Kilgoris. He returned to Nairobi to find that his beloved house in Muthaiga had not been transformed into the Murumbi Institute of African Studies as he had arranged with UNESCO but instead had been demolished and denuded of his indigenous trees which were dear to his heart. It was then he called Elkana from his deathbed and asked Elkana one final request – that Elkana would carve a bird sculpture for his gravesite. When Murumbi died in 1990, his body was laid to rest, alone, in the Nairobi City Park, instead of the cemetery in the City Park which the city authorities claimed was full. He would have been the first African to be buried in that cemetery. He was buried in the Nairobi City Park because his final wish was to be buried as near as possible to his good friend and mentor, Pio Gama Pinto, who was shot dead with a hail of bullets in front of his home inside his small car with his small daughter beside him. Thereafter, Murumbi would wail whenever Pinto’s name was mentioned.

Money designated by the Kenya government for the Murumbi Grave Memorial disappeared. His grave was totally neglected and remains so today, decades later. I have provided a gardener for the graves since Murumbi’s death and only recently the National Museums of Kenya has provided 24-hour guards. On several occasions, would-be thieves tried to dig up his grave thinking there would be loot buried with him. His wife, Sheila, and I placed huge boulders on the grave. When Sheila died, the same thing happened and I moved huge boulders to cover the grave where she lies beside him.

In 2003, I finally set up the Murumbi Trust to rehabilitate the Murumbi collections in the Kenya National Archives which were in a deplorable condition. A few years later, the Murumbi Trust applied for and was granted an acre plot by the Nairobi City Council for what became the Murumbi Peace Memorial. The opening of the Memorial was delayed due to the troubled times in the country in 2007-2008, thus the word PEACE was inserted into the title.

It was then I contacted Elkana and arranged for him to sculpt the bird Murumbi had requested in his final wish. Elkana produced the magnificent “Bird of Peace Emerging from the Stone of Despair” taken from a Martin Luther King speech. It features a multitude of birds and eggs. The Vervet monkeys cavort on it and use it as a slide which probably delights the Murumbis.

However, after Elkana had picked out a lovely 3-ton Boulder of black and white granite from the farm of the late Judge Kasanga Mulwa, marauders stormed the city park and pulled out the stakes surrounding the Murumbi Memorial. Nearby, there were diggers sputtering and chugging, threatening to scrape away the old cemetery and erect apartments on the very same plot that had been granted to the Murumbi Trust. I asked the City councilors if they would first move the bodies or just build over them. I got no response. Then the Director of the National Archives at that time, Lawrence Mwangi, rose to the occasion and informed them publicly that they would take the plot only over his dead body. The developers folded their tents and their diggers and moved on.

The huge granite boulder for Elkana’s Bird of Peace finally arrived at the park courtesy of the Kenya Wildlife Service. Elkana set up camp there and began the long process of carving and smoothing the hard stone.

The Birds slowly emerged from the stone of despair. Well-wishers contributed the black marble base on which it rests overlooking the graves of Joe and Sheila. It was at the opening of the Murumbi Memorial that Elkana got another request from the guest of honor, former US Ambassador, Michael Ranneberger to carve a huge bird for the US Embassy “ Dancing Birds”, now stands to the entrance of the US Embassy at Gigiri.

I implore all of you, on behalf of the memory the late Joe and Sheila Murumbi, to support the heroic pioneer artists like Elkana Ongesa. Elkana is now facing failing health and numerous personal problems along with his ailing uncle Nelson who was the moving force in starting the Kisii stone industry in Kenya as we know it. we have already lost two of the pioneer artists, the late Expedito Mwebe who died while we were funding to buy him a new heart and the late “Africa’s Chagall” the late Jak Katarikawe. Both died impoverished.

I invite all of you to join in the exhibition of recent works by Elkana Ongesa, an exhibition which he will share with the legendary pioneer artists of Tanzania.

The exhibition opens at Nairobi Gallery on March 15th from 2:30 to 5:30 pm.