“Cavalcade”

CAVALCADE

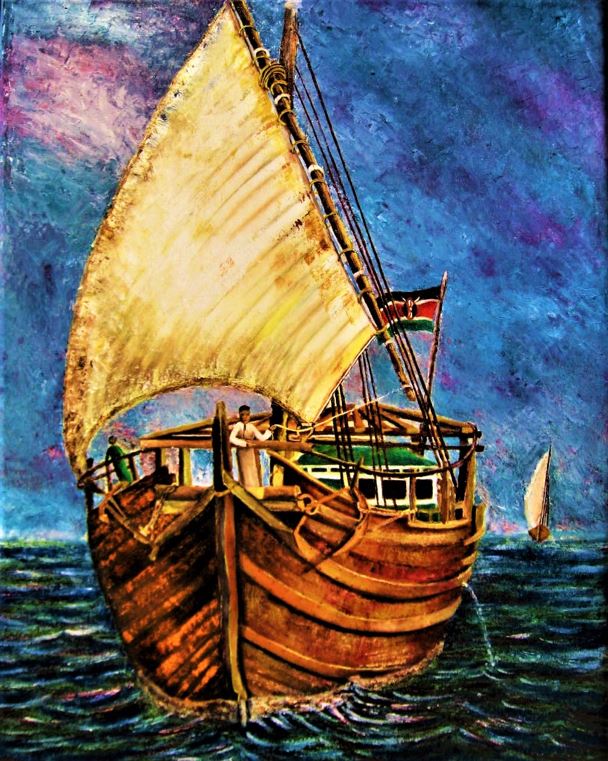

As soon as the monsoon arrives and the “kaskazi” (monsoon winds) becomes established, the visits of dhows to Mombasa increase. At any given time during the Monsoon (December to March along the East Coast of Africa), you will be able to see at least six to seven dhows in the distance. The Captain stands upright on the deck, dressed in a “ghatra” made of fine white cloth. This graceful dhow may be the front-runner of the annual cavalcade of dhows that make their way down the East African coast to trade.

The system of dhows traversing along the East African, Arabian, and Indian coasts had an enormous cultural and economic impact on this area. It made possible a steady flow and interchange of ideas, goods, religions, flavours, and skills.

The dhow, a traditional fishing and cargo vessel, is probably the most iconic symbol of the East African coast of the Indian Ocean. The confusion of ropes and tackle would baffle any landsman. They have one or two masts and a pointed stern. Powered by a single triangular sail originally made of coconut palm leaves (but now of “madrouf”, or rough cotton) and mast originally made of coconut wood and teak from India, they lean into the horizon, a slender yearning profile against the massive skies.

What was especially unique about the original dhows is that the planks were stitched together using rope or coir (a coconut fibre), instead of hammered with nails. But the age-old practice of cotton soaked in coconut oil to stuff any gaps (expanding when wet and keeping leaks out) still survives.

ANCHORS DOWN

Ships have sailed down this Coast for centuries in search of gold, silver, ivory, apes and peacocks. Mombasa is an important terminus for the Arabian dhows. Nowhere else can you see such dhows. “Nakhoda”, the dhow captain standing on the poop decks rasps out orders to his crew to maintain the course of the dhow and later to lower the anchor before running into the port. A Nakhoda who is proud of his dhow will see to it that the sides of his dhow gleam with fresh oil. The reddish-brown colour of this recently oiled ship is very pleasing.

Ships line up neatly at a distance from the port, as they await their turn to dock in. after discharging their cargo at the old harbour, they await their turn to go into the careening area.

CAREENING

The word ‘careen’ literally means to turn the ship on to its side for cleaning and caulking. Nowadays, for the same purpose, the ships are held upright by gin and shear leg supports that are lashed along the ship’s side at high water. Up to a dozen local Swahili boatmen assist with careening, with a drum crew on hand to set up the rhythm for the process. They are demasted and lightened. The sails are taken ashore, usually, to an open space where repairs are conducted. The metal anchor’s cables are greased by hand. The ship’s underwater timbers are carefully cleaned, and necessary repairs carried out. The whole of this part of the ship is then coated with paste consisting of lime and beef fat heated up in metal containers. The paste is applied by hand and not brush and is pressed into any crevices to fill potentially leaky gaps. Finally, a coat of fresh fish oil is applied for waterproofing.

FORT JESUS

Fort Jesus stands over a spur of coral on the coastline near Old Town Mombasa and is recognised as a testament to the first successful attempt by a Western power to establish influence over the Indian Ocean trade. It was built by the order of King Philip I of Portugal Portuguese towards the end of the 16th Century (1593-1596) when Mombasa was a transit place for trade at that time and a gateway to India, and the fort was built to protect the town from outside invaders.

Fort Jesus was captured and recaptured at least nine times between 1631, when the Portuguese lost it to the Sultan of Mombasa. The fort was subject to an epic two-year siege from 1696-98 by the Omani Arabs. The capture of the fort was important for the Omanis to safeguard their empire from Zanzibar and marked the end of Portuguese presence on the Coast. The fort fell to the British in 1895 and was used as a prison.

I wanted to record this UNESCO World Heritage Site from the view of the badans (“samaki” dhows) sailing past before it slowly fades away.

CANALS BETWEEN THE MANGROVES and MANGROVES

On the mainland leading to the south of Lamu Island mangrove swamps appear. Mangroves play an important part in the ecology and conservation of the environment. They prevent mud and beach erosion with their incredible root system. As they are adaptable to saline water, the wood is resistant to insects and wood boring parasites. Lamu’s inhabitants used to build stone houses and mosques using coral stone and mangrove timber.

The roots also reduce tidal currents which causes silt and rotting vegetation to accumulate and thus the area becomes a rich breeding ground for fish and crustaceans. The marine life forms a part of inter tidal food chain.

Coral and sand islands are seen creating sheltered navigable channels. The “poler” in a dugout canoe can take you through these channels where you will never fail to see the little white egrets flying along with you. It is almost like time stands still and you can catch the serene sunset on the return journey.

OFF LOADING

Small Lamu dhows can be seen clustered around the jetty with one or two lying at anchor, close at hand. Names of the dhows and registration numbers are usually painted along the sides of the hull. The coconut matting which covers the sides of this dhow, supported by “boriti” sticks (mangrove sticks), acts as a barrier from the rough seas and winds which helps increase her freeboard speed and keep the cargo in. Much of the cargo is stored in the well of the ship beneath the roof, but a considerable amount also lies on top of it.

It usually takes a full day to offload the cargo, mainly consisting of grains, fish and building materials. The local Swahili men often having an empty sack covering their heads to act as a shock absorber when they are transferring the cargo from the dhow to the jetty. Offloading is followed by a full day of cleaning before taking on the cargo of mangrove timber for the return trip.

Contact Avni on avnishah1962@gmail.com or call +254 734 973207 if interested in any of the paintings above or to place your custom orders

MORE ABOUT AVNI SHAH

Avni is a leading, multi-disciplinary Kenyan artist whose works depicting East Africa will surprise and also delight you with details and a happy colour palette which are the hallmarks in her work. She brings both realism as well impressionism to the scene.

She embarked on her art career after her “O” levels. She attained a Teachers Training Diploma in Art Education from the famous Sir J.J. School of Art, Mumbai. She has done many solo and group exhibitions and two in Germany. Her first mentor Keith Harrington inspired her to capture in her paintings what was old before it gave way to the new resulting in exhibitions titled “Mombasa Old Town”, “Opening Doors To Lamu”, “Scenes Of Kenya”. Some of her latest exhibitions include “Shifting Panoramas”, held at the Village Market in September 2019 and “Across East Africa”, held at the UNON in March 2020. She also took part in FOTA at the ISK in November 2019.

She has worked with world renowned architectural mosaic artist Jim Anderson on broken tile mosaics which are displayed at the local hospitals and one in Addenbrookes Hospital in Cambridge, UK.

Some of the highlights of her career have been “Unusual Friends” and “Wonder of the World” depicting adoption of oryx baby by a lioness in Samburu hang at the Mayor of Berlin’s Parlour and the Kenyan Embassy in Berlin respectively. “At the Water’s Edge” was presented to honourable Charles Njonjo at the relaunch of the Yellow Pages Directory.